The way we communicate impacts our sense of safety

Here’s the next level of nervous system regulation

Many thanks to Gareth, for showing up and chatting to me in the kitchen just when I was open and receptive. Our conversation inspired this piece.

Reminder: Starting this week, I’m putting Connection Hub posts behind paywall (see here for my rationale). Usually, the first section of the post will be free so you can get a sense of what’s it about.

The rest of the post will be locked for paid subscribers. Once a month, I’ll post a whole article for free.

Have you noticed how the company of certain people helps you relax more than others? Some interactions just leave you feeling nourished and calm. Others — seemingly not that different — induce a subtle state of anxiety, restlessness, and unease.

Yet, you don’t understand why.

One explanation self-improvement culture uses is calling people “toxic” or “energetic vampires.” This posits that there are certain types of humans you should avoid. They will drain your energy. They will leave you feeling depleted and generally bring more harm then benefit.

I don’t like that frame of mind. Call me naïve, but I believe most people have good intentions. And even if their impact on you isn’t what you wish, walking away isn’t the only option.

Often, people who make you feel uneasy are those you really care about. And, it’s typically not due to their malintent that you feel uncomfortable. It can simply be certain communication practices they’re using that unconsciously trigger you.

Heck — you may be doing things in your communication that trigger them. This creates a feedback loop where you subtly but surely activate each other’s nervous systems into a threat response.

The good news is that you can learn to notice and negotiate those communication cues. You can shape them that they encourage feelings of safety and relaxation — instead of threat.

This is what I hope to empower you to do with this article. Are you ready for a tour?

How nervous system responds to relational dynamics

As our point of departure, let’s state the obvious.

The way we communicate — verbally and nonverbally — impacts our nervous systems. This is reflected in the levels of comfort and safety we feel with each other.

As noted in the 3 Principles of The Polyvagal Theory, “we naturally, and unconsciously, send signals of safety or danger to each other which either encourage or discourage the reduction of psychological and physical distance that operationally defines social engagement behaviors.”

We’re interconnected — our communication practices and feelings of safety are joined at a hip. The problem is, the communication we exchange is often unconscious and hence hard to put a finger on.

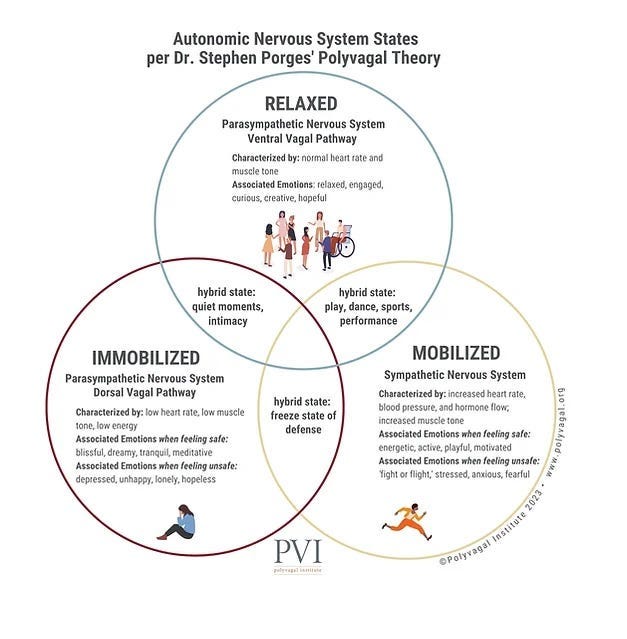

Stephen Porges developed the Polyvagal Theory to describe links between different states of human nervous system and social behaviours. He conceptualized this by describing three main circuits of our autonomous nervous system (ANS): relaxed, immobilized, and mobilized. The mobilized and immobilized get activated when danger is perceived. This causes the body to go into fight/flight, or shutdown response.

The relaxed state induces something Porges calls “social engagement system.” This is when we can feel curious, receptive, and generally open to connection with others. Our nervous system perceives the situation as safe.

It’s not a clear-cut distinction. As you can see below, there are also hybrid states, where the functioning of the circuits overlap:

Let’s think of the mobilized and immobilized states as “threat responses” for a moment. As I’m sure you know from your own life, they often get activated not because there’s actual threat — but because we pick up on something that reminds us of a danger from the past.

It’s helpful to know how to transition yourself back into to a state of safety. This is what’s often called “self-regulation.” Practices such as conscious breathing or muscle relaxation can be helpful for that.

Self-regulation is certainly a great skill, enabling you to lessen the unnecessary stress in your life. But we can’t consider it in separation of the relational context. An article by Elizabeth Clark-Polner & Margaret S. Clark outlines how psychological processes are linked to social context they’re embedded in:

“Consider a simple example: what happens when a beautiful bouquet of flowers is delivered to a woman’s home? How will she react? It depends on relational context. If the flowers come from a suitor to whom she is attracted, and if she has been hoping the attraction is mutual, acceptance of the flowers and joy will result. If they come from her spouse of 30 years who has sent flowers every week for all those years, she will accept the flowers but may have no emotional reaction. If they come from a suitor who is nice enough but in whom this woman personally has no interest, reluctance to accept them, distress and perhaps feelings of guilt may arise. If they come from a person who has been stalking the woman and against whom she has a protective order, she will refuse the flowers and feel fear and distress.

The point is straightforward: behavior, cognition, and emotion depend on relational context.”

In this example, the woman’s response to the same event (receiving flowers) is impacted by her relational context.

Similarly, our ability to self-regulate is tied to communication with those around us. There are certain cues that support our ANS to go into relaxation. Others can reinforce feeling threatened — and, we don’t always understand why.

Our brains constantly scan the environment, looking for safety. However, because of the human brain’s negativity bias, the majority of people are more susceptible to cues for threat than safety. This was historically more adaptive for survival.

What this means is that many of us don’t feel safe “by default” — especially in this era, when our senses are constantly overstimulated, our natural environment altered, and the levels of social anxiety skyrocket. We pick up on small communication cues that activate the mobilized or immobilized response.

That’s why it’s so important that, for the sake of meaningful relationships, we practice intentional, conscious communication. That we intentionally convey to each other: “It’s safe to be with me.”

We’re innately predisposed for co-regulation

I like thinking about co-regulation as an upgraded version of self-regulation.

Instead of relying on your individual willpower, you can fall back on your relationship resources. You still need to make a conscious move towards regulating your nervous system. However, you’re involving another person (or people) in the process.

This is different from being co-dependent, when the other person’s state determines your own.

Rather, co-regulation is something that happens consciously, for your and the relationship’s benefit. It’s something that involves communication — verbal or not.

We’re wired for it since we’re born. As infants, we learn to calm our nervous system in relationship with our caregivers (often the mother, as one who tends to supply more physical touch).

Their demeanor and ways in which they interact with us help us come back to safety. When a parent sings a lullaby or speaks in a soothing voice, a baby sleeps more easily. Conversely, an agitated parent, even if they try to hide their stress, is likely to activate a threat response in their child.

A famous example of how a parent’s and child’s nervous systems interact is the “still face experiment” by Edward Tronick. It illustrates how babies rely on their mother’s expression and engagement for feeling safe. In the video below, you’ll see how after a few minutes of interacting, playing, and responding to the infant’s cues and face expression, the mother’s face goes still as she stops engaging.

She’s physically there with the baby — she just doesn’t interact.

At first, the child tries to reengage the mother in many different ways, including through screeching and loud sounds, as if asking “what’s going on?” But then, as Tronick puts it, “they react with negative emotions, they turn away, they feel the stress of it, they may actually lose control of their posture because of the stress.” Clearly, the baby’s nervous system reacts to the lack of engagement from the mother.

We may think that as adults, we’re different. We’re more in control of our internal reactions, aren’t we? But according to the Polyvagal Theory, this isn’t necessarily true. That’s due to a process called “neuroception” that goes on just beneath the threshold of conscious awareness.

According to Polyvagal Institute, neuroception is “a built-in surveillance system involving higher brain structures that dynamically and continuously interpret information regarding risk that is being transmitted via sensors throughout the body.”

However, for many people, this assessment of risk is faulty. As Porges puts it, “some individuals experience a mismatch and the nervous system appraises the environment as being dangerous even when it is safe. This mismatch results in physiological states that support fight, flight, or freeze behaviors, but not social engagement behaviors.”

Based on our relationship history, we may detect communication cues that remind us of something dangerous from the past. For example, your boss asks you an innocent question about how you’re doing, but due to having been asked this question sarcastically by your school teacher, you perceive it as an attempt to bring you down.

Or, your partner makes a move trying to flirt — but something in their body language reminds you of a time you were assaulted. As a result, your body shuts down while, on a conscious level, you’d expect to feel turned on.

As much as we strive to be emotionally independent and self-sufficient, it’s never fully the case. Because our sense of wellbeing and capacity for survival is so tied to our social connections, we can’t help but pick up on subtle communication cues to determine safety. The big challenge is, those cues are often unconscious.

In the next part of this article, we’ll look at how to bring more consciousness to it. That’s how we can maximize our co-regulation potential. You know what good old Carl Jung said…

“Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate.”

When we become more aware of how we impact one another through communication, then we can do not one, not two, but three very useful things.

First, we can send out less of the unnecessary cues that may cause others to feel threatened.

Second, we can notice when our neuroception is picking up on something that looks like a threat, but isn’t one.

Third, we can learn which cues from others help us feel safe and ask for more of those.

In the next sections, we’ll look at a few examples of everyday communication and how they can reinforce a sense of safety. These are eye contact, touch, and verbal expression of feelings.

On more reason why phone is not your friend

To realize how eye contact impacts sense of safety, I suggest an experiment.

Next time you’re with someone who’s “glued” to their phone, pay attention. When, in the middle of you speaking, they suddenly start scrolling their phone, don’t intervene. Pay attention to your own body and feelings instead.

Notice what happens to our sense of safety and social engagement in that moment.

For me, the immediate response is that I lose track of what I was going to say. I become flustered and sometimes, slightly dissociated. From one moment to the next, I’m not sure what to say or where to look. My muscles, particularly around the chest and stomach, tense up.

On a mental level, the story becomes that they’re not listening because they don’t value our connection. Suddenly, trust is broken. My nervous system goes from relaxed into mobilized — even though, this obviously isn’t an immediate threat.

Why?

There are many possible explanations, but losing eye contact is one of them. The experience of looking into one another’s eyes is vital to feeling safe and connected. That’s because eyes express a lot of nuanced feelings (you can fake a smile but your eyes will give you away!) that inform how the other person is receiving us. Without that reassurance, we easily lose our ground in a conversation.

This was one of the major problems in the pandemic, when suddenly large groups of people were deprived of eye contact. This may well have been one of the immediate causes of mental health deteriorating (I didn’t find research proving this, but many articles on the importance of eye contact would support that claim). I remember it was in 2020 that I deepened my practice of mirror meditation to support my emotional health. A big benefit I got from it was gazing into my own eyes, which became a substitute for eye contact with others!

Eye contact is one of the communication cues that we exchange unconsciously and that can easily help the other person relax. Too much of it may feel too intense and unnatural, causing nervous system activation. This can be particularly true for people on the autism spectrum.

Yet, some amount of it is vital to stay in connection and help each other relax. Because it’s such a personal thing, it may be worth discussing with people close to you what amount of eye contact feels safe to whom.

Touch, and how to speak about it?

Let’s move on to another thing we often exchange freely and unconsciously: physical touch.

Touch can be both a potent soothing tool, or a strong danger trigger in human communication. On the one hand, pleasant touch helps us release oxytocin and contributes to connection. On the other, being on the receiving end of unwanted touch can be one of the most traumatizing experiences.

Besides, it’s not obvious at all which it will turn out to be and when!

A while ago, I was receiving a massage from a woman who only spoke a few words of English. When I was signing up for it, I imagined a purely relaxing, soothing experience. But because of the language barrier, it was difficult to communicate what felt good, what didn’t, or when I needed to shift my position.

Paired up with my tendency to please and appear content, this prevented me from asking for what I needed. I received a massage I didn’t enjoy at all.

Soon enough, my body started shutting down and my mind — dissociating. My nervous system activated the immobilized circuit. I couldn’t bring myself to say anything, anticipating I wouldn’t be understood. All I felt able to do was wait for the massage to finish, and then cried at the end. Worst of all, the woman completely misunderstood my cry, interpreting it as a sign of helpful release… And because of the language barrier, I couldn’t even tell her what happened! 😅

After that incident, I realized how tricky it can be to know for sure how the other person is receiving our touch. Are they feeling genuinely safe and comfortable? Are they uneasy but not saying anything?

Or… are they in a full blown trauma response, frozen and paralyzed, while putting a fake smile on?

This brings us to the topic of consent culture around touch, which is a growing trend — especially in the so-called “conscious communities.” It postulates that when it comes to any kind of physical touch, we need to ask the other person for consent. This applies especially (but not only) to the person who is power-over in a given dynamic, as they may more easily overlook the boundaries of the power-under person.

Additionally, consent culture call us to remember that “saying yes to one act doesn’t imply your consent to others and every act of physical intimacy requires its own consent. If you feel uncomfortable in the moment, you always have the right to stop, even if you previously agreed.”

Consensual touch requires that we do a lot of checking in around what feels safe to the other person, and to ourselves. That’s a great strategy that needs to be promoted in events, groups, and communities, especially where people don’t know each other very well.

With that, I also want to acknowledge there are contexts in which assuming consent for certain types of touch may allow our nervous system to regulate better.

There’s a sense of safety found in liberally touching each other, trusting that (a) we know each other well enough not to have to ask about every single thing, and (b) trusting that the other person will let us know when they’re feeling uncomfortable with what we’re doing.

There’s more layers to that. Some forms of touch may feel new and challenging — but if we’re able to experience them in a safe way, this can open us up to becoming more tactile and connected. Discomfort doesn’t equal threat.

I remember when I first started living with my former housemate, Susannah, the amount of hugs and backrubs she gave me felt slightly uncomfortable. This was mainly because it was new. At the same time, there was an underlying feeling of safety and trust that she was offering that touch with best intentions. And I wanted to open myself to receiving it.

With time, this helped me get more comfortable with touch in general, and feel safe with a wider range of it. But have I strictly followed the consent culture :prescriptions,” I might have missed out on that. I would push Susannah away each time I felt the slightest discomfort.

With touch and physical boundaries, it’s about finding the sweet spot between overly protecting ourselves (that perpetuates the idea that people around us are threats) — and allowing others in too much, which leaves us feeling out of control and violated. How to navigate that with a bit more nuance than just saying yes or no?

One way that Susannah suggested was communicating consent through a “traffic light system,” using just simple colour names: green, orange, red. Green means “I’m enjoying this fully.” Orange stands for “I’m slightly on guard, but I am still happy to explore.” Red means “stop right now.”

This gives a way to efficiently and non-awkwardly communicate physical boundaries as a spectrum, rather than a zero-one game. It can be particularly useful in intimate settings, when you don’t want to break the flow by getting into an elaborate discussion about boundaries.

With touch, just like anything else, we need to acknowledge that we can grow through exploration and experimentation. Fully relaxing touch obviously has a lot of value. But you may also be interested in stretching yourself a little, going beyond your comfort zone — but not into panic.

Naming feelings: how, when, and to what end?

Last aspect of communication I want to mention is a verbal one.

It’s something that the current wellbeing culture emphasizes as a “healthy” way to do relationships. Something that, if you don’t do enough of, it means you’re “emotionally unavailable.” Something that we need to do in order to communicate effectively and humanely.

It is… talking about feelings.

Formulating “I statements” while naming feelings and needs is one of the fundamental principles of Nonviolent Communication. In the past few decades, NVC became widely accepted as the framework to support our nervous systems through difficult conversations.

Additionally, learning to recognize our feelings and name them is empowering. As Marshall Rosenberg, the creator of NVC put it, “when we are in contact with our feelings and needs, we humans no longer make good slaves and underlings.”

It makes sense from the neuroscience perspective, too. Giving names to our emotions may activate the prefrontal cortex and diminish activity in the amygdala, which is responsible for the fight, flight, or freeze responses. On a cognitive level, labeling feelings helps us create a healthy distance between us and the emotions. Giving them names prevents us from identifying with them.

My friend Sílvia Bastos wrote an excellent article about naming feelings as a way to strengthen your mind. This practice is as straightforward as it sounds — to start with, just focus on fishing out one emotion and giving it a name. As Silvia says:

“When I look at my NVC list of feelings and I find the perfect word to describe my emotional state in that moment, I feel a sense of inner peace — the kind of peace that creates movement and progress. (…)

This helps me keep track of what I felt before, and the more I see how much these feelings change, the more I can tolerate and accept them.”

With this, Sílvia points to one more benefit of labeling feelings. When we can name something, it usually means that we’ve experienced it before. We know it. This in itself can make the experience seem less threatening.

All this sounds great in theory. But there’s skillfulness to naming feelings in a way that encourages safe communication. For example, when I described my emotional states to other people (which I do quite a lot!), I discovered it’s easy to slip into overindulging in it.

This can breed secondary, often unhelpful, feelings about the original ones. Especially if the person I’m sharing with isn’t responding in a way I hoped for.

For example, imagine talking about your panic attack and not getting any reassurance or acknowledgment from the listener. This may trigger shame, and when you express it too, that elicits judgement from the other person. They’re becoming impatient about your prolonged emotional share… This can, in turn, trigger anger in you — and so on.

Wasn’t it more helpful to just shut up and process the feelings about your panic attack internally, rather than talking about them?

Maybe. A lot depends, once again, on the social context, and the communication culture you share (or not) with the other person. These will dictate a) how much they respond to your shares in the way you hope for and b) how uncomfortable (or, unsafe) they feel as a result of your shares.

NVC, Authentic Relating, and other practices that encourage emotional conversations are great. But we need to remember they are not a part of everyone’s culture. Often, these are practices of the privileged, who had the comfort and safety enabling them to learn these.

For a lot of people, a direct conversation about feelings can trigger a threat response. Sometimes, taking that into account is more important than talking about your feelings.

Co-regulation through communication: what will you take away?

Now, have I given you clear-cut advice on how to co-regulate through communication?

Obviously not. 😂

In my work around communication and relationships, I found that these topics usually elicit “it depends” kind of answers. Not many things can be advised universally. The ever-shifting social context in which things play out will always demand you to tweak your perspective.

To navigate communication safety is more of an art than science. That’s what life wisdom is for. However, science can help us to at least know what we should pay attention to.

So, if you’re looking for a few key takeaways about co-regulation through communication, I have a few nuggets for you:

The Polyvagal Theory describes three circuits of our autonomic nervous system — and their corresponding social behaviours. Generally, there are three states our nervous system can go into: relaxed, mobilized, and immobilized. The relaxed one is when our “social engagement system” is active and supporting us to make connections.

Our brains are constantly scanning the environment to determine which circuit to activate, based on how safe things appear to be. This process is called neuroception and it can detect both real and perceived threats, depending on our history and conditioning.

A lot of communication cues we convey to one another are picked up on by neuroception as threats — even though these threats aren’t necessarily real. By becoming aware of how communication impacts us, we can exchange those cues more consciously to induce feelings of safety.

Eye contact, touch, and talking about feelings are among most powerful ways to communicate safety or danger. However, they are also ambiguous. A lot of factors go into deciding what seems safe and what doesn’t. We need to take social context into account to understand the impact of these communication cues in any given situation.

Thanks for reading! If you have thoughts or comments about any of these — I’d love to hear them

Sources:

The polyvagal theory: New insights into adaptive reactions of the autonomic nervous system, by Stephen W. Porges

4 Communication Techniques to Regulate Your Nervous System, by Lenni Ferren

Understanding and accounting for relational context is critical for social neuroscience, by Elizabeth Clark-Polner & Margaret S. Clark

The Impact of Nervous System Attunement on Social Anxiety, by Maya Hsu

What is The Polyvagal Theory?, by Polyvagal Institute

Wow Marta, you summarise all of this brilliantly and with such good examples of the neuance. Thank you, wonderful writing, a pleasure to read : )