To elevate your relationships, connect to yourself first

“We can only meet each other as deep as we’ve met ourselves”

Three weeks ago, my housemates moved out. Since then, I’ve been living on my own and enjoying it more than I expected.

I’m remembering that being alone isn’t a nuisance. It’s a resource.

Living, volunteering, and working at a community center for the past 2.5 years, I’ve been surrounded by people pretty much 24/7. That’s an intentional move. I’m treating this period of my life as a “relationship building lab.”

It’s my training period. I believe that connection building skills are among the most important in this century, so I’m keen to learn them.

However, I’m remembering that having good relationships with others it’s not about spending time with lots and lots of people. Equally important is the alone time, when I can nurture the relationship with myself.

That self-relationship is the foundation for how I show up with others.

What is a relationship, anyway?

In this season of my life, I have more diversity in my relational landscape than ever. This is helping me develop what Tasha Eurich called “external self-awareness” — i.e. the awareness of how I’m perceived by others.

One of the most consistent pieces of feedback I hear is how much other people admire my relationship with myself. This is something I heard from friends, co-workers, and events participants alike.

It’s also something that seem to draw people towards me.

Recently, I became more curious about this. How come this is the quality that people notice and highlight the most? What does it matter for others what my relationship with myself looks like?

To answer this, it’ll be helpful to start with the basics. If you’ve read my posts before, you may know that I love re-inventing concepts most people take for granted — and make them my own.

So, this is what we’re going to do here, and answer:

What the heck is a “relationship,” anyway?

We meet a lot of people in our lives, but we don’t have relationships with all of them. Some are one-off encounters — for example, talking to a fellow traveler on a train. Others, we may call “acquaintances” — people orbiting around us, but with whom we don’t interact often enough to call it a relationship. Think a high school friend you never speak to but who “likes” your Instagram posts once in a while.

What is it exactly that makes a relationship different from those occasional encounters?

The Cambridge Dictionary gives a very simple definition of a relationship. It applies to anything, not just human relating. It’s simply “the way in which two things are connected.” The Collins Dictionary gives an explanation that’s a bit more human-specific: “The relationship between two people or groups is the way in which they feel and behave towards each other.”

We could go through countless definitions coined by smart people with titles before their names. Most of those definitions have three common denominators.

1. Duration through time

To have a relationship with someone, you need to have memories of what happened between you and that person in the past — as well as an idea about what the future might look like. Because of that, you’re able to see relationships as a living entity. There’s you, there’s your partner or colleague — and, there’s the relationship between the two of you.

Duration through time makes it feel more tangible and constant than a fleeting interaction on a train.

2. A “space” of certain quality

Even though relationships are constantly changing, we (often unconsciously) attribute certain qualities to them. We may perceive them as “spaces” that we enter whenever we’re with that specific person. Those spaces can be tender, safe, exciting — as well as threatening, uncomfortable, unclear.

In their research, Elizabeth Clark-Polner and Margaret S. Clark refer to this as “relational character.” They write, “Just as there are many aspects of an individual’s personality, so too are there many aspects of relational character that vary across, as well as within, relational types.”

3. Expectations

Each relationship usually involves expectations. Typically, this means having some idea of what might happen between you and the other person. Relational expectations are the foundation of trust.

For example, you wouldn’t expect your partner to push you through the window in the middle of a fight. If you did, you probably wouldn’t choose to be with them. Your expectation of what could and couldn’t happen between the two of you has to be tolerable to you.

When those expectations are more or less aligned with reality, that makes a relationship durable.

A relationship with yourself includes elements analogical to relationships with others. The difference is, you are on both the receiving and giving end of the relationship. You are relating to yourself — it’s at the same time meta, profound, and a bit absurd.

Let’s look at the beautiful absurdity how our outer reality reflects the inner one.

Relationship with Self… or Selves?

Often, the connection to yourself is understood as a communication channel with “your true self.” I see this concept as misleading and unhelpful.

For those familiar with the Buddhist philosophy, it’s not news that the idea of self is considered an illusion. Neuroscience confirms that — so far, we haven’t been able to find the place in the human brain where some “true self” resides.

In my own journey of various self-awareness practices, my “true self” seemed to always be taking on a new shape. That’s why, today, I’m much more sold on the idea of “multiple selves” (or parts) talking to each other. That conversation is what creates my relationship with myself.

In her Substack, Sara Ness wrote about authenticity as a “city of different selves.”

“It’s huge, sprawling, filled with alleyways and shops that you could never explore in a year of looking. The city has many entrances. It belongs to you, and you have spent many years exploring it. The city changes often, and as soon as you learn one part, others have already changed. (…)

People ask you about the city in which you live. You’re not sure what to say. What part of the city do you tell them about? How can they expect you to sum up your authenti-city in just a few words?”

Your “relationship to self” can be helpful to conceptualize as an emergent process.

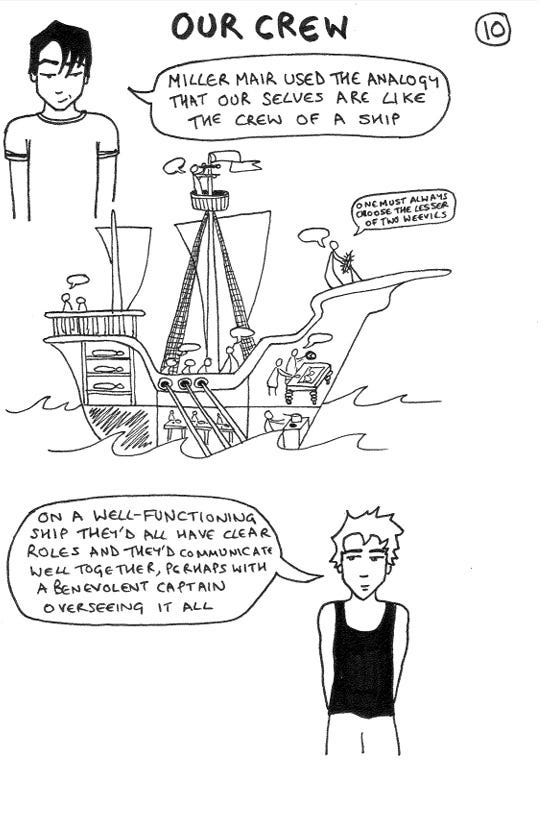

It can be akin to exploring a city. Or, a conversation of different parts. Or, a ship that is managed by a crew, where everyone has a role to play.

That latter metaphor is sometimes used to visualize the main idea of Internal Family Systems (IFS).

IFS is a therapeutic approach that “conceives of every human being as a system of protective and wounded inner parts led by a core Self.” IFS has gained popularity in recent years — in my opinion, because it frames self-identity in a flexible, open-ended way. This is in line with more fluid and less constrained social identities that we now have available.

The bottom line?

Getting to know any person — including yourself — isn’t about getting to know a static entity. It’s not like reading a book or watching a movie that remains unchanged when you come back to it.

Rather, it’s more akin to drawing your own image by connecting dots on paper. It’s an active, creative process. Each dot represents a different part of the self and the lines— the ways in which those parts interact.

If we stay with the ship crew metaphor, we can go even further. Not all members of the crew have equal power. They can be efficient if one central relationship is healthy and active.

That is the collaboration between the captain and the first mate of the ship. To meet them, we’ll look at a model of two selves — the cognitive and the somatic one.

The collaboration between your inner captain and first mate

The work of Stephen Gilligan has been obscured from my view until recently, when my partner gifted me his book. The inspiring title — The Courage to Love — drew me in.

Since then, I’ve become increasingly curious about what Gilligan calls “the self-relations” approach.

his framework is coherent with the IFS in that the self isn’t seen as one entity. As Gilligan phrased it, “relationship is the basic psychological unit.” Feel into that for a moment: relationship is the foundation, not the aftermath, of the self.

Instead of talking about multiple parts (like in the IFS approach), Gilligan speaks of a “relational” self as an collaboration of two entities: a somatic and a cognitive self.

They are the ones in charge of your ship.

The somatic self is connected to the direct sensory experience of the world, which is largely inherited from our ancestors. It’s the “nature” part of the self. The cognitive self develops over time and, as Gilligan puts it, is “based more in social-cognitive-behavioral language, makes decisions, meanings, strategies, evaluations, and temporal sequences. It develops a description of one’s competencies, preferences and values.”

This concept isn’t new. It’s the idea of “taming” your life energy by using the conscious, analytical, and evolutionarily most recent part of the human brain.

In the language of Sigmund Freud, it could be called the id-ego relationship. For William James, it would be the horse-rider metaphor (or elephant-rider for Jonathan Haidt). In Hindu cosmology, it’s the Shakti — Shiva union of consciousness, also understood as the relationship between the feminine and the masculine.

It doesn’t matter what names we give to these two selves. The important part is how they collaborate— or, what the cognitive self makes of whatever the somatic self brings in.

In Gilligan’s approach, this is called “sponsorship.” The cognitive self’s task is to “sponsor” the somatic with compassion and love. This is what transforms our raw, bodily experiences into ones full of purpose and meaning.

Loving sponsorship the crux of a strong relationship with yourself. It can then informs positive patterns in relationship with others.

Let’s look at a mundane example.

Imagine you’re on a coffee date with your partner, and they start talking to an attractive barista behind the counter. Your somatic self is immediately at play. You feel heat in your chest, as jealousy and insecurity arise. There’s not much you can do about it — it’s just a spontaneous, instinctive response.

The skillfulness in relating to yourself will be reflected in the response of your cognitive self. How are you going to receive that primal experience of jealousy? What kind of self-talk will fire off? What conclusions will you walk away with — and, what behavior patterns will get reinforced as a result?

One option your cognitive self has is to induce shame. You may criticize yourself for being jealous in the first place. “Really, are you so insecure to care about a minor thing like that?!” — could be a self-critical thought you have in the moment. As a result, you’d walk away with feelings of self-disappointment and, likely, try to suppress jealousy in the future.

This is unlikely to lead to more connection with yourself or your partner.

A more loving response of the cognitive self may be to get curious about the jealousy. It could look like, first, validating the emotion and allowing the somatic self to experience it.

Then, the cognitive self may inquire:

Why are we feeling this so strongly?

Does it have to do with something from our childhood?

Did our partner cross any boundaries here?

Is this something to communicate out loud, or something to investigate inwardly for now?

What’s likely to result from that kind of response is less identification with the jealousy and more relational resilience in the future.

The more skillful the relationship between your cognitive and somatic self, the more it translates into positive relationships with others. You develop capacity for compassion when you see it play out in your inner experience.

The conclusion?

“We can only meet each other as deep as we’ve met ourselves”

We’re coming full circle here. By now, you may be starting to see that your relationship to self is essentially… a playground for all relationships.

Regardless of what lens you put on: the Internal Family Systems, Stephen Gilligan’s frame of the cognitive and somatic self, or simply seeing “self” as a collection of different parts — the key is to start perceiving your internal experience as a relationship.

From there, you build capacity to hold other people’s experiences in your awareness. The more different parts of yourself you meet, the more space you have for people who are, seemingly, very different from you.

It’s as the heading of this section reads: we can only meet each other as deep as we’ve met ourselves. This exact wording is a quote from Fia’s song, A Journey Unfolding (Beautiful song, by the way — have a listen).

But the same idea shows up all over the spiritual literature, self-improvement blogs, and scientific research. The capacity for holding and understanding yourself is pivotal for other relationships.

This has been particularly well-documented in studies of the therapeutic process.

One study posits that self-awareness of a therapist is a better predictor of their results than supervision or the theoretical knowledge they have. Another research paper opens with this statement: “The personal self who is the therapist is an essential element of the therapeutic process, because it is the human relationship with clients that is the medium through which the work of therapy is done.”

All this goes beyond just a therapy setting and extends to all interpersonal relationships.

Knowing yourself means you become more comfortable with intricate details of the human experience. You tap into the essence of what “being human” means. You know how to invite intimacy with others, because you regularly experience that intimacy with… yourself.

When people appreciate my “good connection to myself,” I can see how it impacts them. I can see this when I acknowledge my inner experiences out loud — and bring them inside the relationship. I can (not always but often) name that I feel embarrassed, reveal my thought process behind a decision, or give context for why I unintentionally caused pain.

I think this makes my friends see me as honest, accepting of myself, and therefore — safe to be with.

I’ve known for a while that spending time alone was good for me. But now, I see it doesn’t benefit just me.

Thanks to the community around me and the feedback I got, I understand that connecting to self is also key for better relationships. So, I’m not bailing out on those solitary, long autumn evenings that await.

I can be without housemates for a while — knowing that I’m building capacity for deep relationships with the future ones.